- Home

- Helen Dunmore

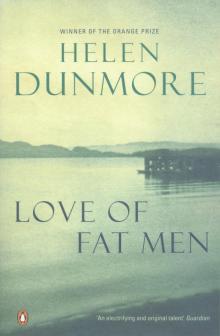

Love of Fat Men

Love of Fat Men Read online

Helen Dunmore

LOVE OF FAT MEN

Contents

Love of Fat Men

Batteries

Short Days, Long Nights

The Bridge Painter

Spring Wedding

Annina

The Ice Bear

The Orang-utans and the Angry Woman

Païvi

The Thief

Ullikins

A Grand Day

Family Meetings

North Sea Crossing

A Question of Latitude

Your Body Next to Mine

Smell of Horses

Cliffs

Girls on Ice

Follow Penguin

PENGUIN BOOKS

LOVE OF FAT MEN

Helen Dunmore is a novelist, short-story writer and poet. Her novels are Zennor in Darkness, awarded the McKitterick Prize in 1994, Burning Bright, A Spell of Winter, winner of the 1996 Orange Prize for Fiction, and Talking to the Dead. All these novels are published by Penguin. Her poetry collections include The Sea Skater, winner of the Poetry Society’s Alice Hunt Bartlett Award, The Raw Garden, a Poetry Book Society Choice, and Secrets, winner of the 1995 Signal Poetry Award. A selection of her poems can be found in Penguin Modern Poets 12.

Helen Dunmore was born in Yorkshire and now lives in Bristol with her husband and children.

Love of Fat Men

LOVE OF FAT MEN. Ulli would like to go and see a film with this title. She would buy herself a fistful of Panda liquorice and a daytime ticket and sit there and watch it through again and again, until the usherette sent for the manager. And another good thing about films is that people who are of average weight in real life look dense, almost majestic, once they are on film. Because the camera loves absences. Flesh that isn’t there. Hollows under cheekbones. A shadow under the jaw which writes a whole false story of intellect and suffering into the face of a man who spends all day wondering whether he has done right to have both ears pierced, or should he have left it at one?

Speaking of earrings, she loves them too. She thinks of a man who was in a promising way to be fat one day. For now he makes do with a curve of the jowl, a faint trace that time will roll out in flesh. Around his lips there is a gloss of oil. He has always just finished eating spaghetti. And not cheap dried macaroni either. He has a pasta machine in his kitchen. He strips off long ribbons of slippery translucent dough and coats them in virgin green olive oil and eats them just as they are. He says it is a waste of time trying to make sauce with the tomatoes they grow in this country, which are only fit for throwing at politicians. Instead of this he makes anchovy spaghetti and tagliatelle with pesto for his friends, which they eat with strong sharp wine. An hour or two later they are hungry again. His name is Lucca, like the city. Or at least, this is what he calls himself. He has a family which is even more secret than her own. But she hopes that she will not discover one day that Lucca has a mother and father sitting in a one-bedroom apartment in the outskirts of Helsinki, dreaming of their summer house, and visits from Lucca. She likes small lies to remain as they are, seductive, growing their own flesh out of hints and silences. What a tombstone it would make, too. Here lies a liar.

Ulli knows she isn’t Lucca’s type. But he is fond of her. He is her friend. Ulli’s not being his type means that he can come round to her room and sprawl on her bed eating packets of macaroons or Danish pastries which he has bought at a cake shop in the city centre. He makes quite a long detour in order to buy these particular macaroons, fragile and yet chewy at the centre, flavoured with almonds rather than with almond essence. When Lucca has been spending the afternoon in Ulli’s room, there are crackling crumbs in the bed all night and transparent grease stains on the quilt cover. But she doesn’t mind. He buys tiny triangular apricot pastries for her, and makes better coffee to go with them than she ever makes herself. Come to think of it that is the only time he stands up. When Lucca visits, he lies.

He asks Ulli about what he refers to as her love-life. In the hope that it will stop him using this expression, which she dislikes, Ulli has told him that her own grandmother used to ask exactly the same question, when Ulli was about sixteen.

‘How’s your love-life, Ulli?’

Ulli pictures her love-life as an elusive but rapacious animal which nobody else has ever seen. This is why they keep asking after it.

Lucca always smells so clean. He smells of clean cotton and sharp lemon soap and almonds and vanilla. Sometimes he smells of sugar, but she doesn’t like that so much. Or he smells of garlic and wine, and the parsley he chews after meals to freshen his breath. Lucca is the only person she has ever seen eating a bunch of parsley sprig by sprig. It is full of iron, he tells her. If she eats enough garlic and parsley she will get through the whole winter without flu or a cold.

Ulli is not Lucca’s type, but he likes her hair, because it is long and very soft, with a watery feel to it when it is newly washed. He feels that he could look after it better than she does herself. So sometimes she’ll give it over to him for the afternoon. Her head goes with it of course, but they don’t mind that. She sits on the floor by the bed and Lucca rolls over so that he can spread the hair out over the quilt, lift it and brush it out and run his hands down it, then plait it again. He can do a French plait, and once he has done this Ulli wriggles away from him, because she likes this style and is not able to do it for herself. But as soon as he has done it he always wants to unplait it again, to stroke and weigh and twist the hair into new shapes, to let it drop free. Sometimes he plaits ribbons into it. Sometimes he puts it up and pins it on the top of her head. But it’s too severe for her like that, he says. It will suit her better when she’s older. He tells her how she will look when she is thirty, if she is lucky and things go well for her. He says that she’s lazy and she ought to have her hair trimmed regularly at the hairdresser’s, instead of letting one of her girlfriends snip round the bottom of it with a pair of cheap sewing scissors.

‘It saves money,’ says Ulli. ‘You aren’t going to eat all that macaroon, are you? Let me have the outside bits.’

She is not Lucca’s type, but he says that she reminds him of his sisters. He doesn’t say much about them, but she has the impression that they are a little younger than she is, still at home, three girls with long hair and lively sliding eyes, crammed into one bedroom with pictures of Switzerland on the wall. No pop stars. They like Switzerland, for some reason. The eldest of them is planning to work there as an au pair, before she goes to college. They are all bright girls, Lucca says, much brighter than he is. He says they adore speaking English.

Lucca’s sisters do not live in jeans like Ulli. They make their own clothes: suits and skirts and fitted jackets. Then they lend them to one another, because they are all as near the same size as makes no difference, and they go out on summer evenings in jade-green, in cerise, in butter-yellow, in soft cream. Ulli wonders if they are still virgins. Perhaps they would have to be, in one room. Or perhaps there is a system for sharing the men, as there is for sharing the clothes, so that no one gets over-attached to one garment, or one manner of making love.

Next week, Lucca says, he has been asked to a party in the country about fifty kilometres away. Does Ulli want to come?

‘Will your sisters be there?’ asks Ulli.

‘Of course not! What would my sisters be doing at such a party? They wouldn’t know anybody.’

‘Will I?’

‘Oh, I should think so. One or two. And anyway you’ll like the others. They’ll be your type.’

‘How do we get there? I’m not going on the bus.’

‘I’ve fixed it. We’re borrowing a car.’

‘Whose?’

‘I don’t think you know him.’

‘Come round on the Friday then, and put my hair in a French plait.’

‘Not if you’re going to wear those jeans.’

‘Fine, I’ll wear it loose.’

She stands up and nearly treads on their dirty coffee cups. Lucca smiles at her from the bed. Looking at him from this angle, she thinks that it is a pity she is not his type.

By midnight on Saturday Ulli knows that she’s not going to meet anyone at the party. Only half an hour ago the rooms were thick with dancers. People were spilling out on to the wooden veranda and into the garden beyond to enjoy the mothy dusk of a summer night. Couples drifted under the trees, twining and consuming one another. If you blinked, they were gone.

And they’ve gone. Strangers, acquaintances, lovers, it’s all one now. It doesn’t matter. For those who’ve found somebody, all that matters is now. For those who’ve found somebody the night has narrowed to an intake of breath, and a little pulse of sweat. They laugh with eagerness. They sprawl and ache on the sand down by the shore. They share a cigarette and blur each other’s lips with dry whispers. Ulli steps out on to the veranda and sips from her potent little glass of mesimarja. The dew settles on her bare arms. The rail of the veranda is damp. Its paint peels under her hands. The family is not staying here this summer. There will be a party or two, a weekend, perhaps some sailing. But nobody will have time to sand down the veranda railings and coat them with primer and paint them so that they last through the winter ahead. That’s the kind of job you do when you go to the summer house for weeks on end, the kind of job you do towards the middle of August when the days are already getting shorter and you are starting to think of berry picking and mushroom gathering in the forest. And hauling the boat out of the water to clean the hull. Ulli has never been to this summer house before, but it’s familiar to her as her own breath.

The air smells of raspberries, but it’s still too dark for her to see where they are growing. She takes another sip of her drink. She’s hardly drunk anything tonight, just a couple of glasses of white wine with blackcurrant syrup in them, and now this. She has eaten some birthday cake, a cake with TIMMO on it in dull silver pearls.

Someone whistles. She starts and looks round. A dark shape detaches itself from the door. It’s Lucca. He comes over to her and stands very close, so close that she can smell his white cottony smell, and again the smell of raspberries.

‘We’re going fishing,’ he says. ‘Do you want to come?’

‘Who’s we?’

‘Just me and Timmo. You remember, I introduced you to Timmo. It’s his house.’

‘Why don’t they come here any more?’

Lucca shrugs.

‘The kids are grown up. And his mother’s got something wrong with her. Multiple sclerosis. She can’t get about.’

‘Do you know her?’

‘Oh yes.’

‘It seems sad to leave it like this. The house.’

‘Timmo comes here sometimes.’

‘With you?’

‘Sometimes.’

They walk down the path through the woods, to the little jetty. It is closer to one than twelve now, and the midsummer dawn’s breaking. Timmo is sitting at the end of the jetty. He has cast his line already. The water is so still that Ulli can see his float, scarcely moving.

Ulli sits on the silvery wood, tucking her heels under her. A breeze draws across the surface of the lake, wrinkling it. It reminds Ulli of her mother making jam. She would drop a spoonful on to a clean saucer and blow on it. If it wrinkled, it was ready to pot. Lucca and Timmo speak very softly so as not to frighten the fish. This is the best time for fishing, Timmo says. They sit for a long time, fishing and catching nothing. Ulli is glad. She does not want to see the jetty bloodied with slippery, mauled fish. Lucca has a bar of dark bitter chocolate, which he breaks carefully in three pieces. They eat it, and Ulli throws tiny crumbs into the reedy water under the jetty.

‘Come and sit here,’ Lucca says to her. ‘You can’t see anything back there.’ He shifts sideways and makes room for her.

‘Quite a party, wasn’t it?’ says Timmo.

‘It was fine,’ says Ulli, ‘but a bit too couply for me.’

‘I know what you mean,’ says Timmo. ‘Well, this fishing is a dead loss. Never mind.’

Ulli’s feet are getting cold. She shivers and rubs them together.

‘Parties, parties,’ says Lucca. ‘Turn round, Ulli, and you can put your feet under Timmo’s coat while I plait your hair.’

Timmo sighs and leans back, gripping the rod between his knees. He spreads out a fold of his coat and wraps it around Ulli’s feet. It’s one of those family coats that doesn’t really belong to anyone, and is kept on a peg by the back door for people to grab as they go out of the house to fish or to chop wood in the chill of early morning. It must have been an expensive coat once, but now it’s scored with thorns and berry stains, and the lining’s torn. It smells of moss. A few hundred metres downshore, where a bathing-hut’s rimmed by the sunrise, Ulli sees a flicker of movement. A figure steps out on to a frail-looking jetty, like their own. It bends, unpacking fishing equipment.

‘A serious fisherman, that one,’ says Timmo. ‘He’s down here every morning.’

It’s two thirty. The sun’s fully up now, hazily wrapped in blue. It’s going to be hot again. Why sleep, why go back to the house, why waste a single hour of the summer’s day that’s just joined on flawlessly to the one before, thinks Ulli, as her feet begin to tingle with the warmth from under Timmo’s coat. She smells moss and chocolate and the sharp mineral smell of lake water. Why not stay all day? Later they’ll bathe, the three of them. She’ll find little wild raspberries, so ripe they are almost purple, the sort that dissolve in your mouth leaving only a grainy rub of seed against your teeth. She shuts her eyes.

‘Lucca,’ she says. She’s going to tell him about the day ahead. There’s no need to go home. They can stay here, just the three of them …

‘What?’ asks Lucca, finishing off the plait. Each woven strand of hair is cold and perfect as the scale of a fish.

But Ulli doesn’t answer. She’s already asleep.

Batteries

She looks him dead in the eye.

‘There – are – no – more – batteries,’ she repeats.

His face wrinkles. ‘But you said! You said you’d bought batteries and all. You told us we had to write down everything we wanted on our lists and I did, I made a list and it had batteries on it because I knew I’d need them if I got a Gameboy and –’

‘I did buy batteries,’ she cuts in. ‘They’re all used up. You used them all. None of us knew how quick that Gameboy would go through batteries. You can plug it into the mains, can’t you?’

He stands in front of her, crumpled and reddening. It is 2 p.m. and they have had the stockings, the presents under the tree, drinks before dinner, the dinner. When he crashed into the kitchen for his batteries Paula was putting away the blue and white pudding dishes she’d brought to the cottage all the way from the city so they could have their exotic fruit salad off the china they always used at Christmas. Lychees, passion-fruit, kumquats, starfruit, tangerines with waxy leaves on their stems, glowing slices of mango lapping pineapple on the white platter her mother had left her. She brought the fruit from the city, too, padded in tissue and wrapped in brown paper bags so it wouldn’t ripen too fast. Let other families gorge on heavy puddings.

‘It’s a Gameboy,’ Kay whinges. ‘My Sega plugs into the mains. I don’t want to plug my Gameboy –’

Eric must have caught what Kay was saying. Paula heard his feet quick-padding overhead, up to the bedroom. Now he comes back and stands dramatically in the kitchen doorway, hands behind his back. He smiles.

‘Here’s Father Christmas,’ he says.

The boy’s face changes. It’s all going to start again. Presents and paper and tearing and finding and having and batteries and – ‘That’s it now kids, you’ve had all your presents for this year,’ Paul

a said at midday, when he and Maudie finished scouring under the tree. But she was wrong. Kay shoots her a look and then begins to clamour round his father.

‘Dad, what is it, what’ve you got, Dad –’

‘Hey, hey, steady now. Thought I heard someone asking about batteries,’ and, over his son’s head, to his wife, ‘I guessed this would happen. Those things eat up juice.’ He brings his hands from behind his back and there it is, a white box with a transparent top and four fat cylinders nestled in it.

‘Wow, Dad! A battery charger. Wow, c’n I –’

‘Yeah. Now careful, son, it’s all fixed up. I been charging these batteries since last night.’

Paula watches their two heads duck over the plastic box. Her boy is shining now.

‘Now mind,’ warns the father, ‘it’s for Maudie too.’

‘Maudie hasn’t even got a Gameboy.’

‘She has her Walkman,’ says Paula.

‘That uses different batteries,’ slaps back Kay.

‘Where is Maudie?’ asks Eric, and they look round, and listen. Paula goes to the living-room and there is Maudie, curled in a chair, thumb jammed in her mouth, staring not at the video which is running through for the second time but at the white space of the window. She’s OK. Paula returns to the kitchen. The Gameboy winks, back in command.

‘Will you take that thing out of here,’ she says.

‘You gave it to me,’ mutters Kay.

‘Come on, son, come on upstairs and I’ll give you a game. Your mother’s tired.’

Paula kicks a tired piece of wrapping paper under the table. Batteries. She lets her arms flop on the table, and her head go down. The children hate to see her like this. Two seventeen on Christmas afternoon.

If it was a proper winter they’d be outdoors, skiing. Pack the children into their snowsuits until they’re as fat as bears. Get the four pairs of skis from the shed and go out into the cold blue afternoon, over Silverhill and down to the flats where it was easy skiing for the kids. But there’s no skiing this year. Night after night the ground freezes. It is black and hard a foot deep. Bushes lean skinnily against the wind, dying. They will die without the comfort of snow. On TV they show birds dropping through the pall of frost, dead on the wing. One day parents were warned to keep home their children under ten. Even in the city Paula kept Kay and Maudie home, warmed by the steady breath of central heating, while dossers collapsed in the iron-hard park. Paula’s breath froze on her lips. Her nose ran and the snot made curls of frost. But there was no snow. The sky was hard and cloudless by day. By night it was jabbed by icy stars and a thin wind turned overcoats to cotton. The climate’s changing, people said, as they looked for the snow.

The Ingo Chronicles: Stormswept

The Ingo Chronicles: Stormswept The Deep

The Deep The Crossing of Ingo

The Crossing of Ingo Birdcage Walk

Birdcage Walk Glad of These Times

Glad of These Times Counting the Stars

Counting the Stars With Your Crooked Heart

With Your Crooked Heart Burning Bright

Burning Bright House of Orphans

House of Orphans Mourning Ruby

Mourning Ruby Talking to the Dead

Talking to the Dead Exposure

Exposure Ingo

Ingo The Malarkey

The Malarkey Love of Fat Men

Love of Fat Men The Lie

The Lie The Siege

The Siege Inside the Wave

Inside the Wave Counting Backwards

Counting Backwards The Land Lubbers Lying Down Below (Penguin Specials)

The Land Lubbers Lying Down Below (Penguin Specials) The Greatcoat

The Greatcoat Your Blue Eyed Boy

Your Blue Eyed Boy Zennor in Darkness

Zennor in Darkness Spell of Winter

Spell of Winter Out of the Blue: Poems 1975-2001

Out of the Blue: Poems 1975-2001 Tide Knot

Tide Knot The Betrayal

The Betrayal A Spell of Winter

A Spell of Winter Out of the Blue

Out of the Blue The Tide Knot

The Tide Knot Girl, Balancing & Other Stories

Girl, Balancing & Other Stories Betrayal

Betrayal Your Blue-Eyed Boy

Your Blue-Eyed Boy