- Home

- Helen Dunmore

Glad of These Times

Glad of These Times Read online

HELEN DUNMORE

GLAD OF THESE TIMES

A celebrated winner of fiction’s Orange Prize, Helen Dunmore is as spellbinding a storyteller in her poetry as in her novels. Glad of These Times is full of haunting, joyous and wry narratives. These poems explore the fleetingness of life, its sweetness and intensity, the short time we have on earth and the pleasures of the earth, and death as the frame which sharpens everything and gives it shape.

Glad of These Times was Helen Dunmore’s first poetry book after Out of the Blue: Poems 1975-2001, her comprehensive selection drawing on seven previous collections. It brings together poems of great lyricism, feeling and artistry. It has since been followed by The Malarkey (2012).

‘Dunmore is a particularly lucid writer, and not simply because her poems are so often filled with the play of light. Her language is bare and clean; her forms balladic and unobtrusive… Dunmore seeks to draw attention, not to her mastery of craft, but to her subject and the intricate, original, patterns of her thought…These poems are light-boned, but strong: elegant, complex, fully-turned unions of image, thought and sound. In these times, we should be glad of this voice’

– KATE CLANCHY, Guardian.

COVER PAINTING

Window with Distant Sea by Felicity Mara

COURTESY OF THE ARTIST

Helen Dunmore

GLAD OF THESE TIMES

For Maurice Dunmore

1928–2006

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Acknowledgements are due to the editors of the following publications, in which some of these poems first appeared: Being Alive: the sequel to ‘Staying Alive’ (Bloodaxe Books, 2004), City: Bristol Today in Poems and Pictures (Paralalia, 2004), La Traductière, Light Unlocked: Christmas Card Poems (Enitharmon Press, 2005), The Long Field (Great Atlantic Publications), New Delta Review, Poetry (Chicago), Poetry Review and The Way You Say the World: A Celebration for Anne Stevenson (Shoestring Press, 2003).

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

City lilacs

Crossing the field

Litany

Don’t count John among the dreams

The other side of the sky’s dark room

Convolvulus

The grey lilo

Yellow butterflies

Plume

Odysseus

The blue garden

Violets

The rowan

Barnoon

Getting into the car

Glad of these times

Off-script

‘Indeed we are all made from the dust of stars’

Tulip

Beautiful today the

Dead gull on Porthmeor

Narcissi

Dolphins whistling

Borrowed light

A winter imagination

Athletes

Pneumonia

Wall is the book

Gorse

Blackberries after Michaelmas

To my nine-year-old self

Fallen angel

Bridal

Still life with ironing

Spanish Irish

Cowboys

Below Hungerford Bridge

Ophelia

Winter bonfire

One A.M.

Lemon and stars

Cutting open the lemons

Hearing owls

‘Often they go just before dawn’

May voyage

About the Author

Copyright

City lilacs

In crack-haunted alleys, overhangs,

plots of sour earth that pass for gardens,

in the space between wall and wheelie bin,

where men with mobiles make urgent conversation,

where bare-legged girls shiver in April winds,

where a new mother stands on her doorstep and blinks

at the brightness of morning, so suddenly born –

in all these places the city lilacs are pushing

their cones of blossom into the spring

to be taken by the warm wind.

Lilac, like love, makes no distinction.

It will open for anyone.

Even before love knows that it is love

lilac knows it must blossom.

In crack-haunted alleys, in overhangs,

in somebody’s front garden

abandoned to crisp packets and cans,

on landscaped motorway roundabouts,

in the depth of parks

where men and women are lost in transactions

of flesh and cash, where mobiles ring

and the deal is done – here the city lilacs

release their sweet, wild perfume

then bow down, heavy with rain.

Crossing the field

To live your life is not as simple as to cross a field.

RUSSIAN PROVERB

To cross the field on a sunset of spider-webs

sprung and shining, thistle heads

white with tufts that are harvest

tended and brought to fruit by no one,

to cross the long field as the sun goes down

and the whale-back Scillies show damson

twenty miles off, as the wind sculls

out back, and five lighthouses

one by one open their eyes,

to cross the long field as it darkens

when rooks are homeward, and gulls

swing out from the tilt of land

to the breast of ocean – now is the time

the vixen stirs, and the green lane’s

vivid with footprints.

A field is enough to spend a life in.

Harrow, granite and mattress springs,

shards and bones, turquoise droppings

from pigeons that gorge on nightshade berries,

a charm of goldfinch, a flight of linnets,

fieldfare and January redwing

venturing westward in the dusk,

all are folded in the dark of the field,

all are folded into the dark of the field

and need more days

to paint them, than life gives.

Litany

For the length of time it takes a bruise to fade

for the heavy weight on getting out of bed,

for the hair’s grey, for the skin’s tired grain,

for the spider naevus and drinker’s nose

for the vocabulary of palliation and Macmillan

for friends who know the best funeral readings,

for the everydayness of pain, for waiting patiently

to ask the pharmacist about your medication

for elastic bandages and ulcer dressings,

for knowing what to say

when your friend says how much she still misses him,

for needing a coat although it is warm,

for the length of time it takes a wound to heal,

for the strange pity you feel

when told off by the blank sure faces

of the young who own and know everything,

for the bare flesh of the next generation,

for the word ‘generation’, which used to mean nothing.

Don’t count John among the dreams

(i.m. John Kipling, son of Rudyard Kipling,

who died in the Battle of Loos in 1915)

Don’t count John among the dreams

a parent cherishes for his children –

that they will be different from him,

not poets but the stuff of poems.

Don’t count John among the dreams

of leaders, warriors, eagle-eyed stalkers

picking up the track of

lions.

Even in the zoo he can barely see them –

his eyes, like yours, are half-blind.

Short, obedient, hirsute

how he would love to delight you.

He reads every word you write.

Don’t count John among your dreams.

Don’t wangle a commission for him,

don’t wangle a death for him.

He is barely eighteen.

Without his spectacles, after a shell-blast,

he will be seen one more time

before the next shell sees to him.

Wounding, weeping from pain,

he will be able to see nothing.

And you will always mourn him.

You will write a poem.

You will count him into your dreams.

The other side of the sky’s dark room

On the other side of the sky’s dark room

a monstrous finger

of lightning plays war.

As clay quivers

beaded with moisture

where the spade slices it

the night quivers.

Late, towards midnight, a door slams

on the other side of the sky’s dark room.

The spade stretchers

raw earth, helpless to ease

the dark, inward explosion.

Convolvulus

I love these flowers that lie in the dust.

We think the world is what we wish it is,

we think that where we say flowers, there will be flowers,

where we say bombs, there will be nothing

until we turn to reconstruction.

But here on the ground, in the dust

is the striped, lilac convolvulus.

Believe me, how fragrant it is,

the flower of coming up from the beach.

There in the dust the convolvulus squeezes itself shut.

You go by, you see nothing, you are tired

from that last swim too late in the evening.

Where we say bombs, there will be bombs.

The only decision is where to plant them –

these flowers that grow at the whim of our fingers –

but not the roving thread of the convolvulus,

spun from a source we cannot trace.

Below, at the foot of the cliff

the sea laps up the apron of sand

which was our day’s home. Where we said land

water has come, where we said flower

and snapped our fingers, there came nothing.

I love these flowers that lie in the dust

barefaced at noon, candid convolvulus

lilac and striped and flattened underfoot.

Crushed, they breathe out their honey, and slowly

come back to themselves in the balm of the night.

But a lumber of engines grows in the seaward sky –

how huge the engines, huge the shadow of planes.

The grey lilo

The grey lilo with scarlet and violet

paintballed into its hollows, on which

my daughter floats, from which her delicate wrist

angles, while her hand sculls the water,

the grey lilo where my daughter floats,

her wet hair smooth to her skull,

her eyes closed, their dark lashes

protecting her from the sky’s envy

of their sudden, staggering blue,

the grey lilo, misted with condensation,

idly shadows the floor of the pool

as if it had a journey to go on –

but no, it is only catching the echo

of scarlet and violet geraniums,

and my daughter is only singing

under her breath, and the time that settles

like yellow butterflies, is only

just about to move on –

Yellow butterflies

They are the sun’s fingerprints on grey pebbles

two yards from the water,

dabbed on the eucalyptus, the olive,

the cracked pot of marigolds,

and now they pulse again, sucking

dry the wild thyme,

or on a sightless bird, not yet buried

they feast a while.

If they have a name, these yellow butterflies,

they do not want it; they know what they are,

quivering, sated, and now once more

printing sun, sun, and again sun

in the olive hollows.

Plume

If you were to reach up your hand,

if you were to push apart the leaves

turning aside your face like one who looks

not at the sun but where the sun hides –

there, where the spider scuttles

and the lizard whips out of sight –

if you were to search

with your small, brown, inexperienced hands

among the leaves that shield the fire of the fruit

in a vault of shadow, if you were to do it

you’d be allowed, for this is your planet

and you are new on it,

if you were to reach inside the leaves

and cup your hands as the fruit descends

like a balloon on the fields of evening

huffing its orange plume

one last time, as the flight ends

and the fruit stops growing –

Odysseus

For those who do not write poems

but have the cause of poems in them:

this thief, sly as Odysseus

who puts out from Albanian waters

into the grape-dark Ionian dawn,

his dirty engine coughing out puffs of black,

to maraud, as his ancestors taught him,

the soft villas of the south –

The blue garden

‘Doesn’t it look peaceful?’ someone said

as our train halted on the embankment

and there was nothing to do but stare

at the blue garden.

Blue roses slowly opened,

blue apples glistened

beneath the spreading peacock of leaves.

The fountain spat jets of pure Prussian

the decking was made with fingers of midnight

the grass was as blue as Kentucky.

Even the children playing

in their ultramarine paddling-pool

were touched by a cobalt Midas

who had changed their skin

from the warm colours of earth

to the azure of heaven.

‘Don’t they look happy?’ someone said,

as the train manager apologised

for the inconvenience caused to our journey,

and yes, they looked happy.

Didn’t we wish we were in the blue garden

soaked in the spray of the hose-snake,

didn’t we wish we could dig in the indigo earth

for sky-coloured potatoes,

didn’t we wish our journey was over

and we were free to race down the embankment

and be caught up in the blue, like those children

who shrank to dots of cerulean

as our train got going.

Violets

Sometimes, but rarely, the ancestors

who set my bones, and that kink

where my parting won’t stay straight – strangers

whose blood beats like mine –

call out for flowers

after the work of a lifetime.

Many lifetimes, and I don’t know them –

the pubs they kept, the market stalls they abandoned,

the cattle driven and service taken,

the mines and rumours and disappearances

of men gone looking for work.

If they left papers, these have dissolved.

Maybe on census nights they were walking

fr

om town to town, on their way elsewhere.

Where they left their bones, who knows.

I can call them up, but they won’t answer.

They want the touch of other hands, that rubbed

their quick harsh lives to brightness.

They have no interest in being ancestors.

They have given enough.

But this I know about: a bunch of violets

laid on a grave, and a woman walking,

and black rain falling on the headstone

of ‘the handsomest man I’ve ever seen’.

The rowan

(in memory of Michael Donaghy)

The rowan, weary of blossoming

is thick with berries now, in bronze September

where the sky has been left to harden,

hammered, ground down

to fine metal, blue-tanned.

In the nakedness beneath the rowan

grow pale cyclamen

and autumn crocus, bare-stemmed.

Beaten, fragile, the flowers still come

eager for blossoming.

Weary of blossoming, the rowan

holds its blood-red tattoo of berries.

No evil can cross this threshold.

The rowan, the lovely rowan

will bring protection.

Barnoon

The Ingo Chronicles: Stormswept

The Ingo Chronicles: Stormswept The Deep

The Deep The Crossing of Ingo

The Crossing of Ingo Birdcage Walk

Birdcage Walk Glad of These Times

Glad of These Times Counting the Stars

Counting the Stars With Your Crooked Heart

With Your Crooked Heart Burning Bright

Burning Bright House of Orphans

House of Orphans Mourning Ruby

Mourning Ruby Talking to the Dead

Talking to the Dead Exposure

Exposure Ingo

Ingo The Malarkey

The Malarkey Love of Fat Men

Love of Fat Men The Lie

The Lie The Siege

The Siege Inside the Wave

Inside the Wave Counting Backwards

Counting Backwards The Land Lubbers Lying Down Below (Penguin Specials)

The Land Lubbers Lying Down Below (Penguin Specials) The Greatcoat

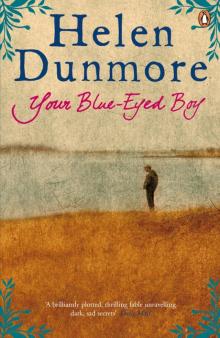

The Greatcoat Your Blue Eyed Boy

Your Blue Eyed Boy Zennor in Darkness

Zennor in Darkness Spell of Winter

Spell of Winter Out of the Blue: Poems 1975-2001

Out of the Blue: Poems 1975-2001 Tide Knot

Tide Knot The Betrayal

The Betrayal A Spell of Winter

A Spell of Winter Out of the Blue

Out of the Blue The Tide Knot

The Tide Knot Girl, Balancing & Other Stories

Girl, Balancing & Other Stories Betrayal

Betrayal Your Blue-Eyed Boy

Your Blue-Eyed Boy