- Home

- Helen Dunmore

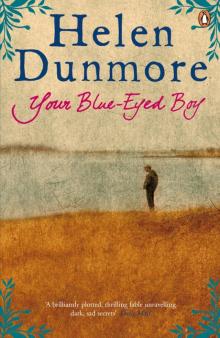

Your Blue-Eyed Boy Page 2

Your Blue-Eyed Boy Read online

Page 2

‘Did you go back?’ she asked suddenly.

He stooped, picked up a stone, let it fall in the deep water. The ripples rocked then seemed to swallow themselves, to make the pond still again.

‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘He’s still in the basketball hoop, right? Slipping down with his own weight and it’s getting tight. And he’s scared now, but I think he’s trying not to make a noise in case we come back. Those big bug eyes staring at me. Even more scared now I’d come back. And I got up on the packing-case and I tried to lift him out of there but I couldn’t. He was too heavy. And I wasn’t as tall as Jimmie Walsh. I’d haul him up and he’d slip down and each time it would be harder to pull him up again, out of the hoop. Then he started making this little noise like he couldn’t hold it in any more. I looked at his face and it was twisted up and there was stuff bubbling out of his nose. He didn’t know why I was lifting him up. It was like he believed I wanted to –’

Michael paused.

‘You were trying to help him, but he didn’t know it,’ said Simone.

‘Yeah, well,’ said Michael. ‘I guess he saw it another way. Fuck it. Why would I think of it after all this time?’

The camera. Calvin lifts the camera.

‘Hey, man, lemme get my jeans on,’ protests Michael. There is a thin grey blanket over Michael and Simone. It has slipped down over Simone’s breasts but she is too embarrassed to pull it up again. Besides, she’s used to Calvin coming in like this.

‘Good picture,’ says Calvin, squinting at the viewfinder. ‘Go-ood picture.’

Simone sneaks a glance at Michael. He’s smiling, enjoying this.

‘You got flash on that thing, man?’ he asks.

‘Sure. You want me to take some pictures?’

‘What do you think?’ Michael asks, turning to Simone with that look of false, teasing solicitude that only comes on his face when Calvin is here. ‘You’ll be going back home to England soon, won’t you? How about some pictures to take back with you?’

Simone opens her mouth. Just in time, she stops herself from bleating out, ‘I’m not going back’ in front of Calvin. Calvin mustn’t see what Simone hopes for. She pictures the winter wind flailing round the cabin in town, a fire lit and Michael striding in. He shakes the snow off his shoulders, his face softening as he sees Simone stitching his shirt-buttons on, the lamp-light a pool of melting gold on her hair. His voice is charged, husky.

‘Simone –’

The two of them, the closed door. Nightmare relaxing into dream.

Calvin knows nothing. He doesn’t hear Michael at night, roused from nightmare, clutching at her hair, her breasts.

Simone says nothing. She pleats the edge of the blanket and waits for Michael.

‘Yeah,’ he says, ‘yeah.’ He reaches over Simone, and takes the edge of the blanket. Slowly, looking her straight in the eye, he peels back the blanket.

‘Michael!’ she protests, snapping her legs together. But he pulls the blanket right away to the other side of their bed.

‘Cool,’ says Calvin. ‘That’s cool.’ His spidery outline dances over them. The snout of the camera protrudes this way and that. ‘You look beautiful, man.’

A little stringent part of Simone comes to life, wonders if this is singular or plural, then dies down again to the dormancy where it’s spent the whole summer. The camera probes the white triangle that Michael’s swimming shorts don’t cover. The stir of his genitals. Their flesh touching, thigh to thigh. Simone rolls a little sideways to present the safe hairless curve of the classic nude. Calvin is much too close now, on top of them. The camera flashes, blue and white. She flinches, expecting a sound, a crackle like thunder.

‘Relax, baby. Relax,’ says Michael. He rolls her back. The camera shoots again and again. Suddenly Michael coils and gets up, stands beside Calvin. ‘Lemme see, man.’ Calvin passes him the camera, and Michael peers at the viewfinder. Simone flinches. Calvin is making Michael see what he sees.

‘You need to get closer,’ says Calvin.

‘No closer,’ says Simone.

‘Please baby. Listen. It’s OK if it’s me taking the pictures, hunh?’ wheedles Michael.

Calvin folds his arms, watching, as Michael takes the camera and kneels down in front of Simone.

‘What do I do, Cal? Do I press here?’

‘You gotta change the focus first.’

The two men kneel, intent on the gadget.

‘I got it. Hey, relax. It’s me, remember? Come on. You’re so beautiful,’ he croons. You’re a beautiful chick, Simone. Give me a good shot now.’

She hates the language, the language of Michael and Calvin. But his voice melts her. She’s yielding, giving way, spreading her legs for him like she always does. Calvin’s nothing now but a shape in the background, out of focus. The camera flares but this time she doesn’t flinch.

‘That’s it,’ says Michael. ‘That’s the reel finished.’

TWO

I take off my wig and settle it into the shiny box with my name on it, then clip the box shut, reach into the cupboard and put it on the top shelf. My head feels cool and light. I look into the mirror as I comb out my hair. The wig has crushed it flat, so that for a moment my mother’s face peeps back at me. I reach up again, take out the wig, re-settle it on my head. It fits perfectly. It should do. All the measuring we did, following the wig-maker’s diagrams.

‘They haven’t changed this leaflet in fifty years,’ Donald said, poring over it, ‘except to give the measurements in centimetres.’ We stared at the illustrated head. It was lofty, trustworthy, like a phrenologist’s advertisement. Not a familiar head at all.

‘That’s because it’s completely symmetrical,’ Donald said. ‘No human head is like that. Come over here by the mirror and I’ll measure you.’

We had a piece of squared paper and the maker’s instructions. Donald measured me from nape to crown, from crown to chin, over temple and forehead. The tape tickled as it ran over my nose. Donald jotted down each measurement and then read them back to me.

‘It sounds a lot,’ I said.

‘It’s in centimetres, that’s why.’

‘Or maybe I have a huge head. Do it again to be sure. It’s so expensive if we make a mistake.’

The measurements were not quite the same the second time.

‘It’s the tape,’ Donald said, ‘it’s been in your sewing-box for ever. Look how worn it is. Why do we never have decent scissors or tape-measures in this house? And those bloody boys have taken my masking tape again. I wouldn’t mind if they ever did anything sensible with it.’

‘It doesn’t matter,’ I said, ‘as long as it fits more or less. As long as it doesn’t fall off.’ But Donald frowned and compared the figures again. He was always more exact than I was. ‘It’s your hair that’s the problem as well,’ he said. ‘I’m not sure how much I should press down your hair to get the measurements right. These measurements will be geared to men. Their hair won’t be as thick as yours. That’s what the wig-maker will be allowing for.’

I slicked my hair flat with both hands. ‘I’ll hold it down while you measure again.’

‘But that won’t be how you wear it in court.’

His face was very close to me. His skin was fine but I saw the wear on it, the way it crinkled dryly when he frowned. Donald would go on for an hour or more to get the measurements right, and I was tired standing. Since the boys had been born I’d been able to walk any distance but I found it hard to stand still long in one place.

‘Just do it once more and split the difference,’ I said.

He ran the tape round my head, pinched it still with a finger and read off the measurement. Then he looked straight at me in the mirror and smiled.

‘I never thought I’d be measuring my wife for a wig,’ he said. His smile was too open, too fond. It was like hearing him talk of me on the phone, with simple pleasure in his voice. ‘Yes, she’s pretty tired. She’s still getting on top of the job. But she says it’s al

l going well …’ From the next room I would hear the pride and buoyancy in his voice. And then when we turned to one another there was such dark water between us. I looked away.

‘Wait till you see it,’ I said.

‘What do they make it out of?’

‘Horse-hair, I think. It feels like that. There’s an art to it, that’s why there are only these two places that make them.’

‘It should be good,’ said Donald. ‘It costs enough.’

I shut my mouth and let him measure down to my chin again. I was not going to say, ‘You don’t need to worry about that. I’m the one paying for it.’

When the wig came I would have liked to go off by myself to try it on and get used to my face under it, but the boys were there, and Donald too. I unpacked it and held it up. It had tight rolls of horsehair riding on a dense scalp. It looked like an old drag queen’s perm. My family crowded round and Matt snatched up the wig, saying he was going to be the first to try it. Donald took it away from him.

‘Put it on, Simone. Let’s see what it looks like.’

I was wearing jeans and a yellow T-shirt. I knew how the wig would look above them. ‘No,’ I said, ‘I’ll try it later.’

Donald held the thing above my head like a crown. The boys laughed, egging him on. We could have a scene, or I could put the wig on at once, as if it didn’t matter.

‘There,’ I said, settling it on my head. My glance skinned the mirror. The tight band of the wig pressed my forehead and I wondered if Donald had done the measurements right, after all. The boys were staring at me. There was laughter in their faces still, but something else as well.

‘Jesus, Mum,’ said Matt, ‘you look like –’

‘Don’t say Jesus,’ said Donald automatically.

I looked straight into the mirror. My face stared back at me, knowing, severe, aloof. I was of any gender and any time. I was the judge.

‘A judge,’ went on Matt.

‘That’s what she is,’ said my husband, but a faint astonishment coloured his voice. I smiled, then I let my face settle again. This face had no need to please. The wig got rid of my softness, the softness that makes people smile back at me when I’m not aware I’m even smiling.

‘Only a district judge,’ I said.

‘Take it off,’ said Joe. ‘Put it back in the box.’

‘Why?’ I asked him. His eight-year-old face creased with effort, then he said, ‘Don’t wear it at home, Mum. Keep it at work.’

I knew what he meant. ‘It’s all right,’ I said. ‘It’s not something I’ll be wearing about the house.’ Matt muttered something into Joe’s ear and the pair of them began to choke and spurt, farting out laughter.

‘Go on out,’ said Donald.

I touched the wig with my fingers, feeling the tightness and springiness of the curls. They were fixed in shape and they would never unwind.

‘It suits you,’ Donald said. ‘You look good.’

It annoyed me that he talked of the wig as if I’d brought home a new pair of jeans. I knew why he did it. He was afraid of where I was going, away from him. He was afraid of the money I was making, and he wasn’t. He was afraid of the door shutting on him and the children and me walking away with the wig in its box under my arm, to a world of judgments. The outer world where he’d lost his place. I knew how he felt though I never let him know that I knew. I wasn’t sure if he’d realized yet that he might never go back. That work might not ever come back, or the lunches with clients, or the freedom to ring home and say he would be late. He was working from home, that’s what we said. It was only that things were slow. The recession was going on and on. It was better to keep some illusion between us.

‘Judge not,’ said Donald, ‘lest ye be judged.’

I looked at him. I knew he had opened his mouth and the words had come out without him thinking of them. They came from somewhere deep inside that I didn’t share.

‘You got the measurements right,’ I said. We looked at each other: I in my wig, Donald with his brown hair that was nearly all grey now. I thought of how he’d had to fill in some form recently that asked for colour of eyes and colour of hair. And unhesitatingly he’d written ‘brown’. It wasn’t vanity, it was just he didn’t think about himself enough to know that he’d changed. Or so I’d thought as I glanced over his shoulder.

We’d been together so long now that whatever we did out in the world it couldn’t break the conspiracy between us, I thought, smiling at Donald in the mirror as I took off the wig and ran my fingers through my own hair to feel that it was still soft and alive. When I’d met Donald my hair had been down to my waist. Like all men he’d wanted me to keep it that way, even when I knew I wasn’t young enough to wear my hair long any more. He always put his hands in it while he slept at my back, as if he was washing the day off them in my hair. I’d liked it for a long time and then I had stopped liking it.

Now my hair was cut to the level of my chin. I was in that stage of youngishness which seems as if it’ll go on for ever, but I knew from other women how quickly and suddenly it can end. And then it seemed as if women entered a climate of invisibility. I would go out to meet that end. I’d wear the wig and no lipstick. I would be the judge. If I grew pouched and heavy, it would only add to the command in my face. I could go on for ever, almost. I was thirty-eight years old.

I hang my gown on the hook inside the door, and brush down my skirt and jacket with the flat of my hands. The cupboard smells of new, blonde wood. As its door swings the little mirror inside fills with blue sky and a brief dazzle of midday sun, then empties again to show my face. I am smiling. My face is soft. I lean in close to the glass, and pick a speck of mascara out of the corner of my eye with my forefinger. I am the face of the law here. It’s nothing personal.

The first time I noticed the clerk of the court move back against the wall to let me pass I wondered what on earth he was doing. He had his arms spread against the wall as if to make more room. I smiled at him, then I realized that he was giving way to me because now I was the judge. It was nothing to do with me. An abstract respect for an abstract thing which was walking in and out of this courtroom in the temporary outfit of my flesh. You have to understand that right from the start or you fall in love with yourself, as I’ve seen some judges do. Not my sort of judge, not little district judges who handle the small cases. We are only doctors in surgery, watching the minor ills of the world pass in and out and trying to decide what to do for the best. And slowly coming to realize that we can’t do all that much, no matter what judgment we give. But there are some High Court judges who can’t separate themselves from the deference. They get as itchy for attention as old actors. They test their power by seeing how much people will put up with. And then add to that the odd one who dreams of a comeback in the greatest role of all, black cap on head, pronouncing life or death.

When I was first in court and frightened, I used to imagine the judge clipping his toenails. Can you imagine sitting in a shop window to have your toenails cut? It’s much more personal than having your hair washed. You’d have to know someone pretty well before you’d let them see that little pile of horny yellow clippings, like rind.

You watch the judge. I used to watch that shifting and clenching of the buttocks during a long sitting, which probably meant he had piles. And now I suppose people are doing the same to me, trying to look past the wig and find a human being inside.

I’m in chambers all afternoon, starting with a bankruptcy petition. I don’t like bankruptcies. This is where people end up when they’ve gone through the hoop, to have the stamp put on them. Bankrupt has a terrible sound to most people, though for some it’s a matter of getting it over, waiting three years and starting again. Sometimes I see them looking at me while we pick over the wreck of borrowing and hoping and not quite getting enough time and creditors starting to press. It has a slow-motion quality, like an accident you’ve already had in your dreams. But no matter how slow, it can’t be stopped. They look at me as if

they’re helpless to put that landslide of debt into words. Or they look at me if to say What does she know? They think I’ve had it easy. The sharper ones guess it’s probably been made even easier for me, because there’s pressure to get women into the judiciary now. But most of them don’t think anything. It’s as much as they can do to get through this, the petition for bankruptcy against them. They’ve charged themselves up to come here, and there’s a strange relief in it too, that the terrible thing they’ve sweated over night after night is actually happening.

Two weeks ago a man looked at me at the end of the hearing. He cleared his throat, then he said, ‘I’m sorry.’ He wore a tidy dark suit, like the suit a haulage contractor might wear to Mass on Sunday. He was big in his suit. He would have worked for other men for years before he was able to start up on his own. For years it had gone well. The business had expanded, and he’d moved to a bigger house. Then when things started to slip, and he’d have liked to sell the house to get hold of some of the money that was tied up in it, there weren’t any buyers. By the time he could sell it was all owed to the bank anyway, and more.

He wasn’t one of those who can put the blame elsewhere and hold tight to the thought of starting again in a few years, when things pick up. To him, it was a disgrace. You could see it in the way he stood and listened to what was being said. He had very bright blue eyes. I knew that he was forty-seven, but apart from those eyes he looked much more. He still had years to go, with this on top of him, pressing him down. If he was lucky he could get back to working for someone else, but looking at him I doubted it. There was still assurance in his body, as if it didn’t yet know what his mind knew. He was braced to cope with the bankruptcy hearing, not with what lay beyond it.

It doesn’t take very long. When I’d made the order and it was over, he should have gone out of the room after the usher, but he didn’t. He cleared his throat and stood there and said, ‘I’m sorry.’ I think his voice came out louder than he meant it to do. He wasn’t speaking to the solicitor for the other side or even to me. It was something in him that could not bend to what had happened, that kept on taking responsibility even when all the responsibility had been taken away from him. He was the kind of man whose wife would never have had to sign a cheque. She’d have to, now. I was afraid of what would happen when he got home.

The Ingo Chronicles: Stormswept

The Ingo Chronicles: Stormswept The Deep

The Deep The Crossing of Ingo

The Crossing of Ingo Birdcage Walk

Birdcage Walk Glad of These Times

Glad of These Times Counting the Stars

Counting the Stars With Your Crooked Heart

With Your Crooked Heart Burning Bright

Burning Bright House of Orphans

House of Orphans Mourning Ruby

Mourning Ruby Talking to the Dead

Talking to the Dead Exposure

Exposure Ingo

Ingo The Malarkey

The Malarkey Love of Fat Men

Love of Fat Men The Lie

The Lie The Siege

The Siege Inside the Wave

Inside the Wave Counting Backwards

Counting Backwards The Land Lubbers Lying Down Below (Penguin Specials)

The Land Lubbers Lying Down Below (Penguin Specials) The Greatcoat

The Greatcoat Your Blue Eyed Boy

Your Blue Eyed Boy Zennor in Darkness

Zennor in Darkness Spell of Winter

Spell of Winter Out of the Blue: Poems 1975-2001

Out of the Blue: Poems 1975-2001 Tide Knot

Tide Knot The Betrayal

The Betrayal A Spell of Winter

A Spell of Winter Out of the Blue

Out of the Blue The Tide Knot

The Tide Knot Girl, Balancing & Other Stories

Girl, Balancing & Other Stories Betrayal

Betrayal Your Blue-Eyed Boy

Your Blue-Eyed Boy